Fights Revivalists, Damnation and a War

I. Charles Chauncy, Foe of the ‘Great Awakening'

He was not unsung in his time, but we must not let him be forgotten.

In 1727, when First Church minister Rev. Benjamin Wadsworth accepted the presidency of Harvard College, Charles Chauncy was called as Assistant to Thomas Foxcroft. Born in Boston, educated at Boston Latin School and Harvard College, he gained the Master’s Degree at age 19. Later in his life, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate from Edinburgh. He was a founding member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. But at age 22, he was the youngest person to be called to the ministry of the ‘Old Brick’ Church. Initially, he continued in the tradition of the early Church, reviving and continuing the great experiment of the founders, preaching piety and disciplined faith, turning to Scripture as the sole authority. But Harvard’s humantistic education was to effect his evolving theoligical, social and governmental views. And Church members did not yet know that he was a thinker and a fighter.

When the ‘Great Awakening’ religious revival of 1741-3 came upon America, these forces seemed to have as their target Chauncy’s style of ‘Old-time’ [formal] religion. In this religious contest, the ‘Revivalists,’ (‘New Lights’) had a reputation for devoting themselves more to ‘enthusiasm’ than scripture. Chauncy’s ‘Old Light’ congregation was faithful to its Puritan heritage of Biblical truth, known as sola scriptura.

Revivalists won the public relations war, while ‘able and learned Preachers’ were disparaged. The evangelists, ‘those of a very different Character,’ were advanced. The most offensive practices of the revivalists’ character included itinerancy (continuous travelling), advertising, and lay exhorting.

They might be compared to the Yankee peddlers of petty goods who ‘lie, cheat and swindle with impunity.’ Furthermore, the advance publicity of evangelists invited ‘settled’ church parishioners to consider an ‘alternative worship experience.’

One ‘Old Light’ minister described how the itinerants periodic visits kept the whole parish in disarray: ‘These Itinerants...screw up the People to the greatest heights of religious phrenzy, and then leave them in that wild state for perhaps ten or twelve months, till another Enthusiast comes among them, to repeat the same thing over again.’ The revivalist’s emphasis on ‘religion of the heart’ was said to give weight to the ‘new birth,’ or private experience rather than the staid, observable, townsmen’s public conduct. The ‘affections’ were endorsed as the ‘seat of salvation,’ elevating inner experience over an

understanding of doctrine. The itinerants proposed that one submit to this ‘awakening,’ and allow it to assume control of one’s spiritual life, even if it meant leaving the parish church!

By 1743, Charles Chauncy, in his sermon, Seasonable Thoughts on the State of Religion in America, averred that some good might come out of this religious fervor, but that it ‘countered the manner in which God dispensed his grace in a usual, predictable, orderly way.’ He asked his First Church members not to be taken in ‘by the immoderate claims that characterize the revivalists’ reputation and publicity.’ He saw much evidence of ‘enthusiastic Heat,’ and a ‘commotion in the passions.’ But the result did not show ‘that men have been made better.’

By 1743, Charles Chauncy, in his sermon, Seasonable Thoughts on the State of Religion in America, averred that some good might come out of this religious fervor, but that it ‘countered the manner in which God dispensed his grace in a usual, predictable, orderly way.’ He asked his First Church members not to be taken in ‘by the immoderate claims that characterize the revivalists’ reputation and publicity.’ He saw much evidence of ‘enthusiastic Heat,’ and a ‘commotion in the passions.’ But the result did not show ‘that men have been made better.’‘Tis not evident to me that Persons, generally, have a better Understanding of Religion, a better Government of their Passions, a more Christian Love to their Neighbur, or that they are more decent and regular in their Devotions towards God.’

Chauncy held that all Christians should insist on a ‘due Care to prove All Things’ by Biblical standards and right reason. He especially mistrusted the evangelists’ conversion accounts. He thought that they were based on ‘secret Impulses’ rather than on ‘the written word’ and the ‘Rule of Conduct.’ He and his ‘Old Lights’ were wont to say that ‘none are converted but such as know they are converted and the time when.’ The revivalists had slipped into the same error as the Antinomians: the belief that personal experience transcends ‘scripture and reason.’

Chauncy believed itinerant preachers were the great instrument of ‘Religious Mischief.’ At its center were self-styled miracles. Its history reached into the dark past of pagan superstition. Its leaders produced results through means designed to manipulate weak-minded people, and its publications were highly partisan.

Chauncy’s sermon, ‘Some Seasonable Advice to those who are New- [born again] Creatures’ showed that this current ‘religious stir’ had turned New England religion on its head.There would be ill effects from this undue emphasis on the New Birth. Chauncy was against a conversion that granted instant and complete grace. Converts should rather expect to slowly grow and increase in faith. This process takes time and diligence. Evangelists preached a ‘so-called’ Revival of Religion. Chauncy would have a Revival of Discipline to combat this confusion and disorder, and thus promote ‘true’ religion.

Chauncy’s sermon, ‘Enthusiasm Describ’d and Caution’d Against’ cast him against ‘hell-fire and damnation preaching.’ The itinerant evangelist practiced this style to the exclusion of everything else. Chauncy’s style in his sermons was a calm, logical approach. He counselled using the ‘four gifts of the Spirit.’ The first gift aids in setting forth the truth in a clear light. The second gift was to ‘use a good voice, good pronunciation and elocution.’ ‘Becoming gestures’ and a graceful air will sufficiently move the passions. The third gift serves to touch the conscience of the sinner. The minister must preach enough terror to rouse sinners from their security. Sinners are awakened by fear.

The last and most useful gift is to ‘speak comfortably to distressed sinners.’ In ‘mild, tender and compassionate terms, set forth the loving-kindness of GOD in JESUS.’ In the ‘four gifts,’ Chauncy makes it clear that to insist on a single method is to question the wisdom of God, who has ‘provided for diversity.’ With these gifts, Chauncy rests his case for the ‘Old Lights.’

The English evangelist, George Whitefield preached a strict Calvinist view of election. ‘Going to Heaven’ meant salvation by God’s predestination. Chauncy supported ‘free will’ to effect one’s salvation. Whitefield, himself an itinerant evangelist, induced ‘transient conversion’ or ‘enthusiasms.’ Chauncy, in contrast, supported the settled ministry of the educated clergy.

In a spontaneous meeting between the two eminent clergymen, the following exchange took place:

‘I see you have returned to Boston, Rev. Whitefield.’ ‘Yes, Rev. Chauncy, indeed I have.’

‘Well, Rev. Whitefield, I am sorry to see it.’ ‘And so is the Devil, Mr. Chauncy.’

II. Charles Chauncy’s Theological Progression

Enlightened Universalism. Rational faith. Reason and scripture.

‘You expect to look down from heaven upon numbers of wretched objects, confined in the pit of hell, and blaspheming their creator forever. I hope to see the prison-doors opened; and to hear those tongues, which are now profaning the name of God, chanting his praise. In one word, you imagine the divine glory will be advanced by immortalizing sin and misery; I by exterminating both natural and moral evil, and introducing universal happiness. Which of our systems is best supported, let reason and scripture determine.’

— Charles Chauncy: The Mystery Hid from Ages and Generations, or, the Salvation of all Men; the Grand Thing aimed at in the Scheme of God

.

Chauncy, a New England liberal in the Arminian tradition, did not believe that one lived a religious life merely to attain salvation and its consequent life in the world to come. Chauncy saw religious life as one of moral progress. With his commitment to logic and reason in theology, strict bible study with critical and historical analysis, with moral aspiration as the focal point, Chauncy was able to conceive a religion which would form the basis of a movement taking on the name of Unitarianism.

Chauncy had earlier contended against the emotional preaching of ‘enthusiast’ evangelists. He believe that their abandonment of reason left them beyond the possibility of correction. Since they believed that truth had come to them from the Spirit, they took the attitude that ‘they are certainly in the right and know themselves to be so.’ This conviction of absolute certitude in their opinions caused them to be ‘not only infinitely stiff and tenacious, but impatient of contradiction, censorious and uncharitable. They encourage a good opinion of none but such as are in their way of thinking and speaking.’

Chauncy believed ‘real religion’ to be sober, calm and reasonable, and to provide an ethic of character building and self-cultivation, another touchstone of the liberal movement in theology.

Salvation of all Men (or Universal Salvation) was known and discussed among Boston ministers from the 1750s. It was not published until 1784, but marked a major shift in theological thinking. The results are shown in the 1786 Declaration of Faith which replaced the original 1630 First Church Covenant. Gone were such burning issues as covenant theology, visible saints and the conversion experience. In a now Enlightened congregation, early Puritan piety declines. This is a document which anticipates a movement toward Unitarianism:

‘I. We, whose names are underwritten, declare our Faith in the one only living and true God.

II. We believe that the Lord Jesus Christ...was sent to redeem us fromall iniquity...to purify a peculiar people zealous of good works. III. We believe in that gospel, the only rule of our faith and practice.United by the ties of One Lord, one common Faith, and one Baptism, we promise to live in Christian love; to watch over each other as members of the same body; to counsel and assist, whenever there shall be occasion; to be faithful to our master, and faithful to each other, waiting in joyful hope of an eternal happy intercourse in the heavenly world.

All who acknowledge the divine authority of the gospel, ought to observe its positive institutions. We remove every obstacle, which may prevent those who worship, from community with us; we impose no other terms of communion than such as are found in the word of God.’

Voted at a Meeting of the First Church in Boston, June 4, 1786 A.D.

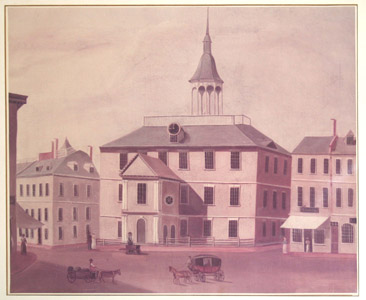

III. Charles Chauncy, ‘Old Brick’

The Rev. Dr. Charles Chauncy stood in the pulpit of the First Church for sixty years, the longest serving and most beleaguered minister of the Seven Societies. Beleaguered from the left and the right. From the left, the ‘Great Awakening’ evangelists were tearing settled churche to pieces. From the right, the Bishops of the Church of England had attempted to establish a base from which to ordain Church of England priests. Chauncy had seen the country through from Calvinism to rationalism and Universalism. Now, as the imposition of more taxes and British military occupation made their threats to civil liberties and freedom, he was to be called upon once more to join sides, to make a stand in the transmutation from Colonial governance to Independence.

He had made a reputation in his bout with the Church of England, and with his exposition of Universal Salvation and its rational study of Scripture. In 18th century Boston, a stubborn character was an important asset. Chauncy expected Bostonians to be self-sufficient, and, as he was to do, to contribute to a national identity.

When his associate, Thomas Foxcroft was debilitated by a stroke in 1762, Chauncy ascended to the leadership of the oldest, most firmly established, most important church in Boston, in the most important city in New England. He was in a position to play a pivotal role in another major issue. Now he was expected to help construct a new country. Here was the clergyman to counter ‘taxation without representation,’ and to effect the change from Colonial status to Independence.

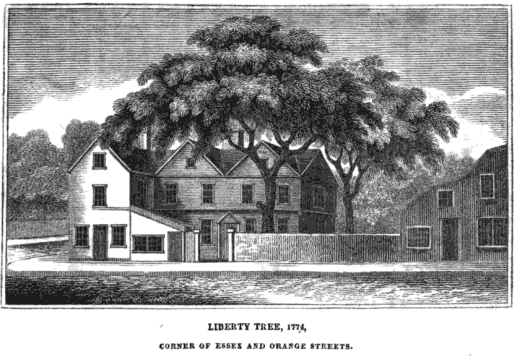

A friend of Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty, Chauncy had lived through and preached radical political views. He knew at first hand the Stamp Act (1765), the Townshend Duties (1767), the initial landing of British troops (1769), the Boston Massacre (1770) — in which James Caldwell, a member of the Second Church had been killed, the Boston Tea Party (1773), the occupation with warships blocking the harbor in the Boston Port Bill (1774), and the erupting event of the War for Independence, the Battle of Bunker Hill (1775).

Chauncy resolutely believed God was on America’s side. His sermon title at the ‘Old Brick’ Church on Election Day morning was, ‘Trust in God, the duty of a People in a Day of Trouble.’ His scriptural justification was in Psalm 22: ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me? Our fathers trusted in thee: they trusted, and thou didst deliver them.’ Chauncy fought his battles from the pulpit, living through a protracted but successful Revolution, just as he had made his determining changes in the Colony’s theology.

The Rev. Dr. Chauncy believed that God made and governed the world; that service to God is in doing good to man. Souls are immortal; crime is punished. Virtue is rewarded, either here or hereafter. He believed in liberty from Calvinism, liberty from a rigid interpretation of the Bible, and liberty from unrepresentative civil government.

‘Old Brick’ Chauncy was as sturdy and resolute a man as the ‘Old Brick’ Church was a building. No wonder ‘The Boston Ministers,’ a popular ballad, had this verse about him:

And Charles ‘Old Brick,’ if well or sick, Will cry for Liberty.

At young & old he’ll rave & scold, He deals in things of State.

A zealous whig than Wilkes more big, In church a tyrant great.

And Charles ‘Old Brick’, if well or sick, Will cry for Liberty.

This ‘broadside’ was possibly sung to the tune Dundee, but ‘Yankee Doodle’ will do as well (or better.)

Sources and further reading:

Pierce (1961), Griffin (1980), Robinson (1985), Lambert (1999).

MORE/ WIKIPEDIA