Witchcraft: Saints and Devils

The Devil Take You!

The existence of the Devil and his practitioners was well documented for Puritans. They would read and wonder about such passages in the Bible: ‘When you enter the land the LORD your God is giving you, do not learn to imitate the detestable ways of the nations there. Let no one be found who practices divination or sorcery, interprets omens, engages in witchcraft, or casts spells, or one who is a medium. For all that do these things are an abomination unto the LORD.’ [Deuteronomy 18: 10] ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.’ [Exodus 22:18]

‘Followers sacrifice to demons, adore them, seek out and accept responses from them, do homage to them, and make with them a written agreement [covenant] through which, by a single word, touch or sign, they may perform whatever evil deeds or sorcery they wish and be transported wherever they wish.’ [A 15th century Encyclical.]

Thus the traditional theological view: the essence of witchcraft was a diabolical covenant, a parody of Christian practice, wherein witches promise to serve devils and devils promise to aid witches. Devils represent an entire order of creation. Thy are confined as punishment to the several miles of dark air above the earth, where they mingle with the tormented souls of millions upon millions of the damned, excommunicated from the company of good angels, who dwell in Heaven near God’s throne.

The Opposing Kingdoms of the Spiritual World

In the belief system of Colonial times, natural forces were overlain by and interwoven with moral, spiritual, and supernatural forces. The supernatural — God’s province — accounted for everything that happens in everyday life. Natural events such as a thunderstorm, were charged with meaning as expressions of Providence, and were open to interpretation as signs of God’s judgment. The moral and the physical concerns, sin and sickness, were interrelated. Puritan belief in the spiritual world, however, posits a duality: the negative spiritual force is represented by the Devil; the positive is represented by Jesus and a living God. To be engaged in the work of the former results in Eternal Damnation; serving the latter leads one to the joys of Eternal Life.

A Faltering Colony: All Hell is Breaking Loose!

During the last decade of the 17th century, a rash of negative conditions existed in the Bay Colony. One found increasing social tensions: contention about the ownership of land, a failing economy and a questioning of the tenets of the founders’ vision. This bred antagonism, suspicion, quarreling, gloom and confusion.

Performing their lay ‘watchman’s duty’, townspeople used the term ‘witch’ as a label to control or punish their neighbors. This epithet was mostly applied to quarrelsome or ‘difficult’ people, those who trespassed on the mores of the community. ‘Witch’ would apply to Quakers who would disrupt Sabbath Gatherings, or walk through the town provocatively unclothed.

Get thee behind me, Satan!

Get thee behind me, Satan!

Though the period of March to December, 1692, an infectious emotional epidemic of ‘witchcraft’ occurred in Salem. It was said that witches were plotting New England’s ruin. In this context, there developed among church people a growing fear of the presence of the Devil as a felt, palpable entity, waiting in each shadow to affect his demonic possession. Salem was widely considered to have been chosen as ‘the battle ground of God against the Devil.’ Haunted children, deluded youngsters with convulsive fits spread contagious hysteria abroad. Young girls formed an ‘accusing circle.’ Townspeople became victims of malicious gossip. Neighbor cried against neighbor.

Rev. Samuel Parris of Salem rose to prominence as the preacher against ‘scandalous immoralities,’ and the teaching of ‘dangerous errors.’ His own daughter, Betty, succumbed to providing ‘spectral evidence of witchcraft.’ Betty became leader of an ‘accusing circle’ who ‘cried out’ on well-to-do and poor alike. No one was safe. A civil court was established to examine, then bring ‘witches’ to trial for their ‘hellish molestation.’ A great number of the ‘afflicted’ grew as ‘fits’ punctually recurred. Girls, matrons and sometimes boys pitted daughter against mother, husband against wife, neighbor against neighbor.’

Wonders

Mass Bay Ministers believed unquestioningly in the invisible world. Without this spiritual dimension, all of theology would be worthless. While they were not directly involved in the examinations or the trials, they did meet as ‘skilled theologians’ to consult on religious implications and to resolve moral dilemmas, particularly that of ‘spectral evidence.’ Revs. James Allen, Joshua Moody and John Bailey of the First Church were generally opposed to the notion of ‘specters.’

Increase Mather of Second Church published Cases of Conscience Concerning vile Spirits Personating Men. In it he comes to a final conclusion: ‘It is better that a Guilty Person should be ABSOLVED, than that he should without sufficient ground of Conviction be condemned. I had rather judge a Witch to be an honest women, than judge an honest woman as a witch.’

Mather’s son, Cotton, had taken young Margaret Rule into his household to perform his typical ‘scientific experiment’ concerning Witchcraft. Cotton’s all-embracing Wonders of the Invisible World records his equivocal stand on the validity of spectral evidence. The world of the spirit was central to his faith and belief. Nor did he condemn the judges who accepted spectral testimony. Later comments by a trial-weary public condemned these views, and Cotton Mather’s name is not cleared to this day.

Repentance

Repentance

After eight months of panic, the colony had grown weary of hysteria, of charges and countercharges, of fear and of pitting neighbor against neighbor. When Lady Mary Phips was placed among the accused, her husband, William Phips, the new Royal Governor, promptly called an end to the proceedings. Rev. Parris, the instigator, was called into question by his parishioners, for ‘He had been a false shepherd who had misled his sheep.’ Critics pointed out that the court had based its judgment on evidence such as common gossip, irresponsible ‘confessions’ and the pretensions of the ‘afflicted girls’ who had given ‘evidence’ on events they had not witnessed. At the trials in Salem, hundreds were accused, 27 were tried, and 20 were executed. Even those who believed in witchcraft had begun to question the procedures, specifically the mass hysteria that surrounded these events. For the 52 people who awaited trial, all but five were exonerated, but many petitions for pardon fell by the wayside.

Rev. John Hale of Beverly, whose wife had been accused, wrote, ‘We have much forgotten what our fathers came into the Wilderness to see. The sealing ordinances of the covenant of grace and church communion have been much slighted and neglected. The fury of the storm raised by Satan hath fallen very heavily upon many that lived under these neglects. The Lord sent Evil Angels to awaken and punish our negligence.’

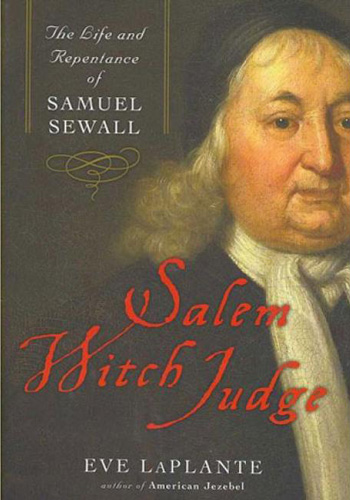

By the new year, ‘God’s Controversy with New England’ had run its course, and there was ‘singing of many hymns relating to the good angels.’ By 1697, a fast day was called as a time to repent the wrongs committed in the tragic witchcraft episode. Many jurors sought to beg forgiveness. Judge Samuel Sewell’s recantation was read as he stood in church meeting. It was said that ‘the Lord had chained up Satan.’

But no one was considered wholly innocent in the outrage which had held the populace in the vise of collective guilt. Many questioned whether theocratic influences had swayed the examiners and the judges to take on the prerogatives of God as Judge over men’s souls.

Reconciliation

In its 1702 session, The General Court of Massachusetts declared ‘witchcraft examinations,’ especially the use of spectral evidence, to be unlawful. Yet a plea by the remaining survivors that their names be cleared went unanswered. From 1709 to 1711, state officials appropriated sums to recompense survivors for seizure of lands or for prison fees. Closure on the ‘War of the Righteous vs the Unrighteous,’ however, did not occur until the twenty-first century.

In the summer session of the Massachusetts State Legislature in 2001, the General Court exonerated the last five of the forgotten ‘Salem witches.’

Sources and further reading:

Oldridge (2002), Reis (1997), D Hall (1991), M G Hall (1988), Silverman (1984), Kors & Peters (1972), Starkey (1969), C Mather.